How We Know Bitcoin Is Not a Bubble

The Value of Money

No matter how many times Bitcoin grows by orders of magnitude, holdouts still remain who argue that it is a bubble destined to fail. To address this claim, I will describe a theory that describes how to appraise Bitcoin according to the Austrian theory of money.

In Austrian economics, money is valuable because it is liquid. This means that a given value of money is demanded everywhere and can easily be traded for goods. For example, say I had enough bitcoins to buy a 100-oz gold bar. In late 2010, this would have been worth around one to two million bitcoins and would have been impossible to sell on the open market without drastically affecting the price. By contrast, in early 2014, 100 ounces of gold was worth about 100 bitcoins, and this amount could easily have been traded quickly on one of the major exchanges without affecting the price noticeably. Thus, in early 2014 Bitcoin was more liquid than in late 2010, and was therefore a better currency.

Unfortunately, this insight about the value of money does not give us a means of appraising it because the liquidity cannot be separated from the price. This is kind of a problem—it sounds like a circular argument because it says that Bitcoin’s value is caused by its price! This allows for no way to detect whether Bitcoin is overvalued or undervalued.

In order to prevent this model from being causally circular, a time element is required. Our observations about money come from the past, whereas our judgments about its value are about the immediate future. This makes the value of money into a positive feedback loop. If the network is growing, then it will tend to continue to grow, whereas if it is shrinking, it will tend to continue to shrink.

This model of money has no independent quantity that estimates anything like an underlying value. Any price is as good as any other—the only thing that matters is the direction it is moving. This is not really an appraisal after all—but it is still the right way to understand Bitcoin’s price.

Bubbles

In the short term, there is money to be made by buying anything whose price is showing an upward trend if one spots the trend early enough. In other words, if one can predict that other people are likely to appraise a good more highly in the future, regardless of whether that appraisal is rational or irrational, then it makes sense to buy into the change of sentiment. If lots of people begin to think this way, then they can create a positive feedback among one another and bid up the good beyond any rational appraisal of it. This is a bubble.

A bubble bursts because eventually people have to get around to using a good for its ultimate purpose. Once it is understood that the people who actually use the good are being bid out of the market, then the price crashes because people stop predicting higher and higher appraisals to the price.

Money, however, need not have any ultimate use. It may only ever passed around from person to person, without ever being consumed. A stock is valued by the sum of its interest-adjusted dividends. A bond is valued by its redemption value adjusted by the interest rate and the risk of default. A commodity is valued by the value of the goods it can be used to produce. However, for money, there is no independent quantity to provide a reality check. All money is like a bubble that never bursts.[1]

Metcalfe’s Law

Some of the theory of money can be understood in terms of Metcalfe’s law from computer networking. Metcalfe’s law says that the value of a network is proportional to the square of the number of nodes. The rationale is that the network should be valued according to the number of connections it supports, which is approximately proportional to n_2 (for large _n). Consequently, as the network grows, it presents a better and better opportunity for new members. As new members enter, the network improves for all its present members.

Metcalfe’s law must be adjusted slightly to apply to media of exchange because some nodes in the trade network will be more valuable than others. Those who have a lot of the medium are potentially able to spend more than those who have little. Therefore, use the market cap of the medium of exchange as n instead of the number of people. Similarly, some transactions are also worth more than others, so it makes sense to use the transaction volume rather than the number of transactions.

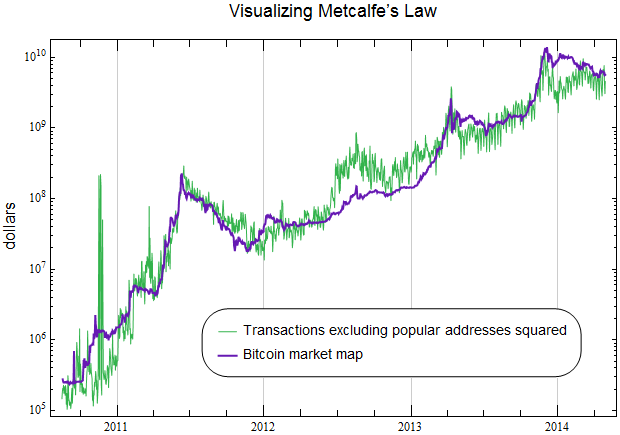

A striking test of Metcalfe’s law in Bitcoin recently appeared on the Bitcointalk forums, created by Peter R. I have made my own chart here.

This chart plots the market cap in blue and the square of the transaction volume excluding popular addresses in green. The axis on the left is the price in dollars. Exactly as Metcalfe’s law predicts, the transaction volume increases very neatly as the square root of the size of the network. The correspondence is beautiful. I wish I had thought to make it first!

I would like, however, to criticize the interpretation of the diagram. On the original Bitcoin Talk, thread, the green plot has been labeled as the “Metcalfe Value”, as if it is an appraisal of the Bitcoin that estimates what it could cost.

This interpretation is incompatible with the theory of the value of money I presented above. In my theory, the value causes the transactions, whereas in the diagram, the transactions cause the value. However, it is only potential transactions that cause the value. Past transactions are of no value to anybody. The current size of the network and the consequent opportunities it is likely to provide tomorrow are what motivate people to buy and sell today.

This may seem like hair-splitting, but a confusion of cause and effect can have serious consequences. For example, many people believe that it is necessary to spend bitcoins and increase the transaction volume in order to make Bitcoin more valuable. Of course this is nonsense; all this does is fill up the network with transactions for things that nobody actually wanted. That does not present a good value for a newcomer because he will want a network that presents him with real opportunities, not just ways of artificially increasing transaction volume. The more that the Bitcoin network is focused on artificially increasing the transaction volume to make it look good, the more it resembles a Ponzi scheme. Rather, to make the network more valuable, we should be hoarders. This is more likely to present newcomers with lots of potential uses for Bitcoin as a medium of exchange.

Appraising Bitcoin

A real good can be valuable because of the ways that it can be consumed or because of the trades that can be made with it. Mises called these causes of value “use value” and “exchange value”. Gold, for example, can be money and used as components in electronics. Evaluating whether a good is a bubble or not requires taking both factors into account; it is not enough observe that the price of a is far greater than can be explained by its use value to conclude that it is a bubble.

To put this another way, suppose that gold was only used in electronics. If that were the case, its price should be expected to be much less than it is now. However, some people started holding gold for longer periods of time before producing anything with it. This would cause the price of gold to go up, which would therefore make gold less useful as an electronics component. However, it would also make gold more useful as a medium of exchange. If gold’s improved exchange value was enough to induce more people to buy it despite its reduced use value, then the price of gold could sustainably continue upwards. Its price chart might look like a bubble, but without the expectation of an imminent crash.

This brings us to Bitcoin. To what extent is Bitcoin’s price a rational appraisal or an investment bubble? The answer is easy, much easier than with a commodity like gold. Bitcoins have almost no use other than as a medium of exchange. Thus, the fact Bitcoin has any price at all is evidence that there is a real network effect and that the cause of its price is its exchange value. With gold one has to consider the interplay between its use and exchange value, but with Bitcoin there is no such confusion:

Any demand for Bitcoin at all is enough to enable it to function as a medium of exchange. If demand continues to grow, then it becomes a better medium of exchange. There is no end to this process because the primary value of Bitcoin is the network effect surrounding it, not any final productive use. Each step in Bitcoin’s growth follows a similar pattern of investment in the coin, improving Bitcoin’s liquidity, creating more opportunity for its use as a medium of exchange, followed by investment in Bitcoin’s infrastructure, thus realizing those opportunities.[2]

Thus, Bitcoin is not a bubble, or at least the available evidence strongly suggests that it is not. Its growth is like a self-fulfilling prophecy: as more people believe in it as a medium of exchange and become willing to buy it, they create the very conditions required of it to make it more useful.

Conclusion

Every time you buy Bitcoin, a fairy gets its wings. Now clap your hands, click your heels together three times, and believe in Bitcoin! It will only take faith the size of a mustard seed.

[Update 5/15/2014: Clarified section ‘Appraising Bitcoin’ in response to criticisms.]

One of the best arguments against the bubble theory of Bitcoin was presented by Peter Šurda in “The Economics of Bitcoin”, in which he asks “What would replace Bitcoin?” The point of the question is that because Bitcoin reduces transaction costs over its alternatives, people have at least some reason to continue holding it until a superior alternative emerges. ↩︎

This analysis leaves something to explain—if the value of a medium of exchange is just the market cap, why does Bitcoin go through hype cycles? Every time Bitcoin goes up in price, that is an increase in its underlying value, so why does its price ever crash? I don’t know the answer, but I think I have a reasonable hypothesis: the network takes time to adjust to the enormous number of newcomers during each hype cycle. Each member of the network adds value, but this takes time—the members of the network must learn something about one another before the value they add to the network is more fully realized. If this effect is real, then the price could temporarily rise more rapidly than the growth that the network can support. ↩︎