Chapter Thirteen

Bitcoin Fixes This

(Originally published on 30 August 2019)

Jackson Hole

Each year central bankers, establishment economists, and talking heads from around the world descend on Jackson Hole, Wyoming to discuss the systemic issues that plague our economy. Constantly searching for an answer but never seeming to find one. It is the perennial Jackson Hole dilemma. There is always much fanfare, and the 2019 edition was no different. Lawrence Summers, former US Treasury secretary and former president of Harvard University, may have best summarized, and inadvertently exposed, the issue with the whole spectacle in a twenty-eight-part tweet thread.[67] Summers questioned a number of foundational assumptions made by the establishment economic mainstream, of which he is a resident member, and also identified many symptoms of economic instability that have become increasingly systemic.

The fundamental question from Summers: can central banking, as we know it, be the primary tool of macroeconomic stabilization in the industrial world over the next decade? Summers doubts that it can. However, he still could not be further from the target. The monoculture of economic thinking in the US believes central banking has a fundamental role to play in creating economic stability. Not just a role but a fundamental one. What tools to use, how, when and to what degree it will be effective is the debate. Central banking is assumed at a foundational level as necessary to achieving economic stability. Even in Summers’s own words, the question “Can central banking be the primary tool?” carries that built-in assumption, with primary being the key word. What the mainstream, including Summers, does not question—nor is it capable of questioning—is whether central banking is the problem rather the solution. Whether it is the primary cause of macroeconomic instability rather than a source of stability.

Historical Track Record

As a historical record, since the financial crisis, central banks have used quantitative easing as the primary tool to help stabilize the economy. Quantitative easing, or QE for short, is a term used to describe the operation of central banks increasing the money supply to “ease” financial conditions. The playbook is as follows: increase the money supply, reduce interest rates, manufacture price inflation, and reflate asset values such that existing debt levels can be sustained and more debt can be created. While central banks use many technical terms, increasing or decreasing the money supply is really the only tool in the tool kit to manipulate interest rates and to effect directional shifts in asset prices.

Despite record-low interest rates today, the global economy has once again begun to deteriorate. Naturally, many are questioning the effectiveness of quantitative easing. What has long been taught as axiomatic is now very much in doubt, but again, there is a critical difference between questioning effectiveness and recognizing that the perceived solution is actually the problem. When taking a closer look into how quantitative easing works, and its consequences, it becomes clear that the function of quantitative easing actually creates the instability it seeks to prevent. It is made worse by the fact that central bankers who have this immense power go back to the same well, time and again, despite having been proven wrong on a wide range of the most consequential matters and without any real function of accountability.

The risk that the economy has entered a substantial downturn appears to have diminished over the past month or so.

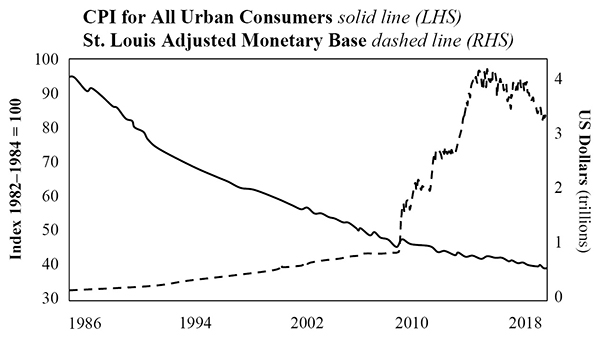

Ben Bernanke famously made this comment three months before Lehman Brothers failed and the first of three formal rounds of QE was introduced as a response to the Great Financial Crisis. QE1, QE2 and QE3 increased the money supply by $1.3 trillion, $0.6 trillion, and $1.7 trillion, respectively. In total, the Fed introduced $3.6 trillion new dollars into the banking system via QE from 2009 to 2014, quintupling the size of its balance sheet or increasing the base money supply fivefold.[69] The merits can be debated but the facts are the facts. Following the crisis, the Fed pursued QE on three separate and distinct occasions, each time in an attempt to stabilize the economy. Setting the technical jargon aside, it is all just money printing. If at first you do not succeed, print more money to stabilize the economy.

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics and Federal Reserve Economic Data (FRED)

While QE isn’t technically “printing money,” the result is functionally the same. The Fed digitally creates new dollars on a ledger (literally out of thin air) and proceeds to use those dollars to purchase financial assets, such as US treasuries (government debt) and mortgage-backed securities. As a net effect, more dollars exist within the banking system in the form of bank reserves that can then be used to lend or purchase other assets. In simple terms, more dollars exist, which causes the value of each individual dollar to decrease. However, the effect is not direct. Instead, it is transmitted gradually through the expansion of the credit system. Said another way, QE creates more dollars and allows banks to expand credit by multiples of each dollar created. This incremental credit (i.e., auto loans, mortgages, student loans, etc.) is then used to purchase goods in the real economy. However, creating money out of thin air does not magically create more goods and services. More base money exists and even more deposits exist as credit is created, which compete for a supply of goods and services that do not and cannot keep pace. That causes the value of the dollar to decline on a relative basis.

Does Quantitative Easing Work?

People often ask whether quantitative easing works. The short answer is no. While many believe that QE was necessary, it merely kicked the can down the road and guaranteed more QE would be necessary in the future. The root cause of the financial crisis was a financial system that had become far too leveraged. At the time, every dollar in the banking system had been leveraged and lent 150:1.[70] There was too much debt and too few dollars. This degree of leverage was only made possible as an indirect function of the Fed sustaining economic imbalances. With every recessionary business cycle in the decades leading up to the crisis, the Fed increased the supply of dollars to lower interest rates and induce credit expansion—similar in operation to post-crisis QE, just much smaller and more gradual. Rather than allow the system to course-correct and reduce the amount of debt as a natural market function, the Fed’s continual response was to provide more dollars in order to sustain existing debt levels and permit further credit creation.

Through this course of action, the Fed inadvertently created the fragility and instability that existed in the financial system in 2008. By pursuing continual credit expansion, an unsustainable degree of system leverage was allowed to accumulate over the course of several decades. While similar policies had been pursued before, the financial crisis created an environment that triggered a more drastic response from the Fed. Simply put, the Fed needed a bigger boat. For context, the cumulative increase in the money supply through QE1, QE2, and QE3 of $3.6 trillion over the five years following the crisis was 36x larger than the $100 billion increase in the five years prior to 2008. This time was different. The real issue was the sustained imbalances in the credit system accumulated over many cycles and the overall degree of leverage. Eventually, the bubble was destined to burst. An exogenous shock to the system was inevitable as a function of time and as the problem became worse with increasing size.

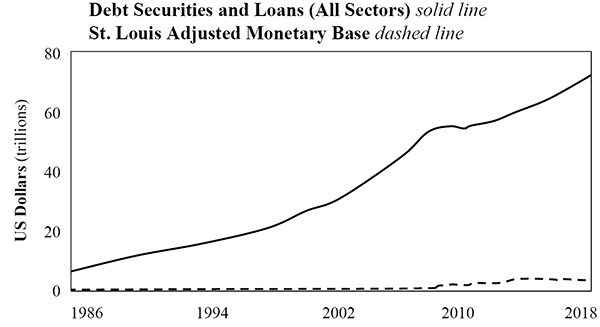

Source: Federal Reserve Economic Data (FRED)

In the Fed’s economy, the credit system became orders of magnitude larger than the amount of base money that existed. As a result, the credit system became the marginal price-setting mechanism rather than the base money. Because the Fed has a mandate to maintain price stability, it must implicitly maintain the size of the credit system in order to sustain general price levels. During the financial crisis, the credit system began to collapse, and asset price levels rapidly declined in a disorderly fashion. To reverse the impact, the Fed was forced to drastically increase the money supply to maintain the size of the credit system, in a way it never had before. However, even after the height of the crisis, the Fed determined it was necessary to add trillions more in new dollars post-QE1 to continue to support a languishing system, despite acknowledging the limitations of its monetary policy tools. This is the Fed’s Catch-22. Even when it seemingly knows better, the default position is to err on the side of more QE, not less. To try again what has not worked in the past to achieve stability. It is the definition of insanity.

I’m perfectly willing to accept the argument that monetary policy is not the main tool, that this is not the main thing wrong with the economy, but it’s our duty to do what we can, to be palliative, to help where we can, even if we can’t solve fiscal, structural, and other problems.

I don’t think it is literally the case that monetary policy is completely ineffective. I think we can see the effects on financial markets, which in turn must be affecting wealth, confidence, and some other determinants of spending and production. To the extent that transmission is weaker, that could be used to argue for more stimulus rather than less stimulus.

By responding with QE, the Fed induced a credit system already saddled with unsustainable amounts of debt to expand massively. Today, the US credit system supports approximately $73 trillion of fixed-maturity debt systemwide, representing an increase of $20 trillion (+40%) above pre-crisis levels (see Figure 6.4). This debt is stacked against only $1.7 trillion of actual dollars that exist within the banking system and $3.8 trillion in total circulation.[73] After years of increasing the money supply, the Fed pursued a reverse operation, gradually reducing the supply of dollars from September 2017 to today. Consequently, there is far too much debt and too few dollars. Because QE induces the creation of ever-increasing amounts of debt, it is more like heroin than an antibiotic. The more that is applied to a financial system, the greater the dependency that develops and the worse off that system becomes when QE is withdrawn. The rhetorical question to ask is: if QE works, why does the Fed always need another round? QE only leads to more QE. Money printing begets money printing, and it is the best empirical evidence to demonstrate that QE does not “work” by any measure.

Bitcoin Fixes This

Prior to 2009, everyone was forced to opt in to this increasingly fragile system as there was no viable off-ramp. The advent of bitcoin, which was launched during the crisis, provided the first credible alternative to opt out, and it exists largely as a response to global QE. While bitcoin would have represented a superior alternative to fiat currencies even in the absence of QE, the global monetary debasement in response to the crisis sharpens the contrast. It is this contrast that makes bitcoin far more intuitive. Bitcoin might technically exist because some highly intelligent individuals identified a problem and set the wheels in motion to create a solution, but it functionally exists because it fixes the problem of printing money.

Given the existing leverage that persists in the financial system, future QE from the Fed (and central banks worldwide) is not merely a possibility. It is a certainty. The credit system was unstable and unsustainable in 2008. As a function of QE, it has expanded massively and now supports $20 trillion more debt in the US alone. Every time the Fed, or any central bank, announces subsequent rounds of QE, it reinforces to the market why bitcoin exists. It also establishes that QE does not work. Market participants are presented with the choice between holding a form of money that is continually and systematically debased by central banks or a form of money with a fixed supply that cannot be printed. Bitcoin is the check, balance, and ultimate opt-out path to the problem QE presents. Bitcoin cannot prevent the printing of dollars, but it is a solution to the same problem.

In “The Pretense of Knowledge,” a speech delivered by Friedrich Hayek at the ceremony awarding him the Nobel Prize in Economics in 1974, Hayek articulates the first principles of why the disparate knowledge of all market participants is greater than that possessed by any single mind. He explains why the dominant macroeconomic theory and monetary policy that guide central banks are inherently flawed through the same reasoning—and why the policy tools used by central banks, such as quantitative easing, create more harm than good.

In fact, in the case discussed, the very measures which the dominant “macro-economic” theory has recommended as a remedy for unemployment, namely, the increase of aggregate demand, have become a cause of a very extensive misallocation of resources which is likely to make later large-scale unemployment inevitable. The continuous injection of additional amounts of money at points of the economic system where it creates a temporary demand which must cease when the increase of the quantity of money stops or slows down, together with the expectation of a continuing rise of prices, draws labor and other resources into which can last only so long as the increase of the quantity of money continues at the same rate—or perhaps even only so long as it continues to accelerate at a given rate. What this policy has produced is not so much a level of employment that could not have been brought about in other ways, as a distribution of employment which cannot be indefinitely maintained and which after some time can be maintained only by a rate of inflation which would rapidly lead to a disorganization of all economic activity.

The speech in its totality, including this excerpt, provides the counter-narrative to the monoculture of today’s economic policymaking. In short, our current system entrusts the allocation of trillions of dollars to just a few individuals. It is not that these individuals lack a significant amount of knowledge. Instead, it is that any small group of individuals necessarily possess far less knowledge than the market of all people who actually make up an economy. Attempting to manage an economy by manipulating the money supply effectively replaces the knowledge of the entire market with that of just a few individuals. The mechanisms that govern supply and demand can no longer function efficiently, which creates imbalances that can only be sustained so long as the market remains manipulated. The financial crisis is patient zero, and the QE response has only left us in a more precarious situation than before. The first-order impact is the devaluation of the currency, but the broader, longer-term impact is the deterioration of the underlying economic structure as a whole.

I don’t believe we shall ever have a good money again before we take the thing out of the hands of government, that is, we can’t take them violently out of the hands of government, all we can do is by some sly roundabout way introduce something that they can’t stop.

Bitcoin may just be the sly roundabout way around the Fed’s economic system that Hayek theorized. Bitcoin creates a system that allows for undistorted economic activity, and it achieves this through a fixed monetary supply governed by a market consensus mechanism. Through this consensus mechanism, bitcoin dispenses with the need for the conscious control of central bankers, relying instead on the distributed knowledge of all market participants. It is also completely voluntary. If you like your financial system, you can keep it (at least for now). However, economic systems converge on a single form of money.[76] And as individuals increasingly opt in to bitcoin, it will only make the issues present in the legacy system more evident. The greater the inclination to store wealth in bitcoin, the lesser the demand to store wealth in the dollar or assets that support the existing dollar credit system. In essence, an increasing shift to bitcoin will impair the supply and demand for dollar credit, accelerating the need for the legacy financial system to rely on even more QE to sustain itself.

While not popular and certainly not accepted by Summers’s Jackson Hole crowd, there is an opposing economic view that argues the very function of a central bank and its active management of the money supply is harmful to the economy. Practically speaking, this view cannot coexist within a central bank because it is antithetical to its primary function. It is why the monoculture came to be and why a different course is never charted. Now that bitcoin exists, however, the monoculture is being challenged credibly for the first time in a long time, and it is no longer merely the subject of an intellectual debate. It is a market test. Two competing monetary systems exist that present a great contrast: one attempts to create stability through active management of the money supply, while the other tolerates interim volatility in the interest of maintaining a fixed supply. Bitcoin provides a credible path to opt out of the legacy system that did not previously exist. It may be volatile, but bitcoin adoption will continue to increase principally for the reason that it represents an alternative that eliminates the ability to create money and actively prevents quantitative easing, the primary central banking policy tool that creates economic instability.

-

Lawrence H. Summers (@LHSummers), Twitter, https://twitter.com/LHSummers/status/1164490326549118976 22 August 2019. ↩

-

Ben Bernanke, “Outstanding Issues in the Analysis of Inflation” (speech), Federal Reserve Bank of Boston’s 53rd Annual Economic Conference, 9 June 2008, Chatham, MA. https://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/speech/bernanke20080609a.htm ↩

-

Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, “Adjusted Monetary Base (DISCONTINUED),” retrieved from Federal Reserve Economic Data (FRED), Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, August 2019. ↩

-

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Z.1 Financial Accounts of the United States: Flow of Funds, Balance Sheets, and Integrated Macroeconomic Accounts, First Quarter 2019, Federal Reserve Statistical Release, 6 June 2019, 7. ↩

-

Minutes of the Federal Open Market Committee, a joint meeting of the Federal Open Market Committee and the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Washington, DC, 9 August 2011. ↩

-

Minutes of the Federal Open Market Committee, a joint meeting of the Federal Open Market Committee and the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Washington, DC, 20—21 September 2011. ↩

-

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (US), H.8: Assets and Liabilities of Commercial Banks in the United States, Federal Reserve Statistical Release, 29 August 2008. ↩

-

Friedrich A. Hayek, “The Pretense of Knowledge,” Lecture in the Memory of Alfred Nobel, 11 December 1974, Stockholm, Sweden. ↩

-

Friedrich A. Hayek, “Exclusive Interview with F.A. Hayek,” interview by James U. Blanchard III, University of Freiburg, Germany, 1984. ↩

-

Reference the essay titled “Bitcoin Obsoletes All Other Money” for a fundamental discussion of why money converges on one medium. ↩