Chapter Eight

Bitcoin Does Not Waste Energy

(Originally published 16 August 2019)

The Long Game

When you board a commercial flight, you always hear the same safety briefing just before takeoff. You may even know it by heart. Every time, without fail, flight attendants instruct passengers to put on their oxygen masks before tending to any children should the cabin lose air pressure. Instinctively, it’s counterintuitive. Logically, it makes all the sense in the world. Make sure you can breathe first so that the child dependent on you can breathe too. The same principle applies to the coordination function of money in an economy and the resources required to protect that function. In a more philosophical safety briefing, the flight attendant might say:

Please make sure the money supply is secure so that we can continue to coordinate the economic activity of millions of people to build these incredibly complex planes that afford you the opportunity to even contemplate the problem I’m about to explain.

We will come back to this, but you can never hope to understand the justification for the amount of energy bitcoin consumes without first appreciating the fundamental role money plays in coordinating economic activity. What is money? How does it work? How should it work? What is its function in society? If you haven’t stopped to ask these questions, you can’t begin to grasp the weight of the problem bitcoin intends to solve. And without an appreciation for the problem, the cost to secure the solution will never seem justified.

Concerned onlookers raise a red flag about the amount of energy consumed by the bitcoin network, without the necessary baseline. The concern stems from the idea that the energy consumed by the bitcoin network could otherwise be utilized for more productive functions or that it is detrimental to the environment. Both fail to appreciate just how critical bitcoin’s energy consumption is. In the long run, there may be no more critical use of energy than that which is deployed to secure the integrity of a monetary network—in this case, the bitcoin network. However, that doesn’t stop those ignorant of the problem from raising concerns.

The fundamentally wasteful nature of bitcoin mining means there’s no easy technological solution coming.

In the context of climate change, raging wildfires, and record-breaking hurricanes, it’s worth asking ourselves hard questions about Bitcoin’s environmental impact.

Bitcoin Energy Consumption

Bitcoin is secured by a decentralized network of nodes (computers running the bitcoin protocol). Economic nodes within the network generate, validate, and relay transactions, as well as validate and relay bitcoin blocks (time-sequenced groups of transactions). Mining nodes perform similar functions while also performing bitcoin’s proof-of-work function to generate, solve, and transmit blocks to the rest of the network. By carrying out this work, miners validate the network’s transaction history and provide a clearing function for current transactions, which all other nodes then check for validity. Think of the clearing function of the New York Fed but on a completely decentralized basis every ten minutes (on average).

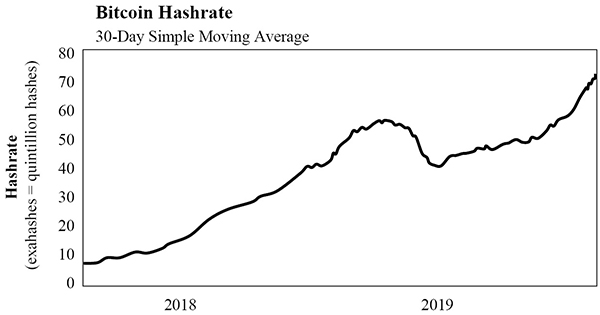

The work performed (running cryptographic hashing functions) requires computer processing power contributed by miners, operating twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week. This processing power requires energy. For context, at 75 exahashes (75,000,000,000,000,000,000 hashes) per second,[40] the bitcoin network currently consumes approximately 7 gigawatts (7,000,000,000 watts) of power, which translates to ~$9 million in energy per day (~$3.3 billion per year), assuming an average cost of 5 cents per kilowatt-hour (kWh) for illustrative purposes. Based on US national averages, the bitcoin network consumes as much power as approximately 6 million homes.[41] By no means is this insignificant, but it is also what secures the bitcoin network.

Source: bitinfocharts.com

How could this much energy usage be justified? And how much energy will bitcoin consume when a billion people are using it? The dollar works just fine, right? Well, that’s just the thing. It doesn’t. These resources are being devoted to fix a problem most don’t understand exists, which makes justifying a derivative cost challenging. People who do not understand why bitcoin has fundamental value are functionally incapable of doing a cost-benefit analysis. Without having any grasp of the benefit side of the equation, it is definitionally impossible. But to help ease the pain of environmentalists and social justice warriors, bitcoin advocates often point out several countervailing narratives to make it seem more palatable:

- Bitcoin will spur innovation in the development of renewable-energy technology and resources.

- Bitcoin consumes energy that would normally go to waste, including natural gas that is flared or vented into the atmosphere.

- Bitcoin consumes only the energy that the free market will bear at a free-market rate.

- Bitcoin consumes stranded energy resources that would otherwise not be economical to develop for domestic or industrial use.

- The nature of bitcoin energy demand will improve the efficiency of energy grids.

These considerations help enumerate why a simple view that bitcoin’s energy consumption is necessarily wasteful or necessarily bad for the environment fails the proverbial test. However, one could never justify the marginal cost without first appreciating the enormity of the monetary problem bitcoin intends to solve. Bitcoin represents a solution to the systemic issues within our legacy monetary framework, and it relies on energy consumption to function. Economic stability depends on the function of money, and bitcoin provides a sound monetary framework that the legacy system is missing, which is why there is no more important long-term use of energy than securing the bitcoin network. So rather than expand on the many individual counterpoints to the mainstream narrative, there is no better place to focus than the first-principle problem: the money problem or the global QE (quantitative easing) problem.

The Function of Money

The problems stemming from our current monetary system are enormous, though most people fail to recognize them. Most experience the symptoms of the problem in their daily lives (working harder for longer, accumulating debt, and still barely getting by) but cannot identify the root cause. To identify a solution, one must first see and understand the problem. The problem that exists is with our money, and the negative impact it has on society is pervasive.

Money is the good that facilitates economic coordination between parties who otherwise would not have a basis to cooperate. It is the good that allows society to function and to accumulate the capital that improves our standard of living—recognizing that capital takes different forms for different people. While some people say money is the root of all evil, Hayek more appropriately describes it as an instrument of freedom:

Money is one of the greatest instruments of freedom ever invented by man. […] If we strive for money, it is because money offers us the widest choice in enjoying the fruits of our efforts.

More specifically, money is the good that allows for specialization and the division of labor. It enables individuals to pursue their own interests. It is how individuals communicate their preferences to the world, whether through work or leisure, and it is what creates the range of choice we all take for granted. Our modern economy is built on the foundation of freedom that money provides—enabling a highly complex and specialized system, which affords a standard of living that prior generations would find hard to imagine.

To simplify the concept, Milton Friedman (expanding on Leonard Read’s 1958 essay[43]) explains the complexity of producing a standard lead pencil. He details how no individual alone is capable of producing and assembling all the necessary resources. The wood, the saw to cut the wood, the steel to make the saw, the iron ore to make the steel, the lead, the rubber for the eraser, the brass ring, the yellow paint, and the glue, etc. Friedman explains how making a single pencil requires the coordination and cooperation of thousands of people, including people who don’t speak the same language, who likely practice different religions, and who may even despise each other if they were ever to meet in person.[44]

If that is just the pencil, now consider the complexity of our modern economy, from cars to airplanes to the internet, and even to your local grocery store. Modern supply chains are so complex and so specialized that they require the coordination of millions of people to deliver any of these basic functions. The orchestration of all the activity that fuels global trade is only made possible through the function of money.

A Living Example: Venezuela

Venezuela provides a tangible macro and micro example of money’s vital role in economic coordination and the dysfunction that follows when it fails. Despite being one of the most oil-rich countries in the world, Venezuela’s currency has recently hyperinflated as an end-game function of monetary debasement. As its currency has deteriorated, basic economic functions have broken down to the point where getting food at grocery stores or critical healthcare is no longer a given. It’s a full-blown humanitarian crisis, and at the root level, it’s a function of Venezuela no longer possessing a stable currency to coordinate economic activity and facilitate production of the goods the country needs to trade.

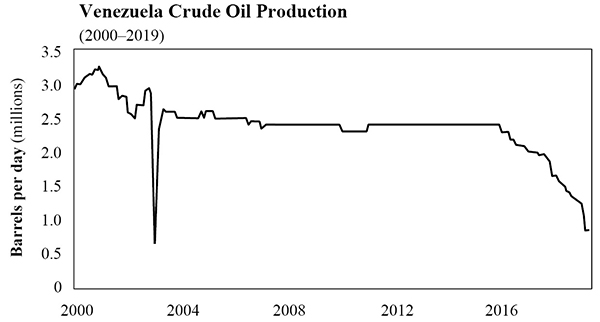

How does this relate to bitcoin and energy consumption? As an energy-rich country, oil was (and is) Venezuela’s primary export, or rather, the principal good it needs to produce in order to trade. Despite its vast energy resources, Venezuela’s oil production has plummeted.[45]

Source: US Energy Information Administration

Venezuela can no longer import the technology or coordinate the resources it needs to extract its primary trading currency—oil. This has caused significant deterioration in its local economy, impairing its ability to produce the electricity needed to power its energy grids, causing extended blackouts, and preventing the delivery of essential services such as power, clean water, or healthcare.

The situation in Venezuela is devastating, and it is a function of the economic deterioration caused by hyperinflation. Monetary debasement distorts the price mechanism of a currency, which creates and sustains economic imbalances. As economic coordination deteriorates, complex supply chains become disrupted, resulting in a decline in the supply of real goods (e.g., food on shelves, oil production, power, etc.) and an imbalance between supply and demand. As more money is created, real goods become scarce relative to the supply of money, which causes the very function of money to break down. Individuals are incentivized to trade out of local currency as quickly as possible as basic goods become more and more scarce, creating a “run” on basic necessities and causing the currency to hyperinflate. This is Economic Deterioration by Monetary Manipulation 101.

The Developed-World Application

Many sitting comfortably in the developed world will look at Venezuela and think it could never happen here, but this ignores first principles. Whether or not it is well understood, the market structure of the Venezuelan bolivar or the Argentine peso is identical to that of the dollar, the euro, and the yen. The Fed may be better at managing stability (for now), but it does not change the fact that the underpinnings of all fiat currency systems are the same. The cost to print or digitally create a US dollar is the same as the cost to create a Venezuelan bolivar—zero. The cost to produce a trillion dollars-worth of either currency is also zero, and the long-term consequence to the viability of the currency is the same.

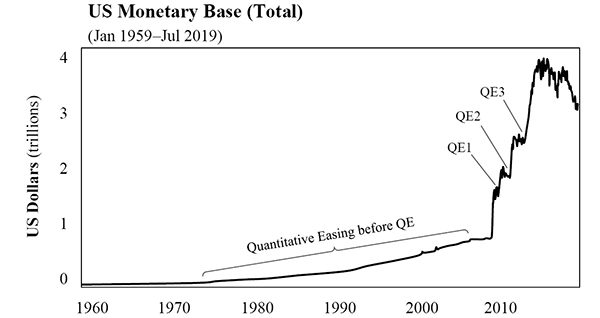

As historical context, the US Federal Reserve expanded the monetary base from $190 billion in 1984 to $840 billion at the beginning of 2008, an increase of $650 billion over twenty-four years. Then, in response to the 2008 financial crisis, the Fed increased the money supply by nearly $3.6 trillion over the subsequent five years to a peak of $4.2 trillion in 2014.[46] The debasement occurred gradually until the financial crisis, which then resulted in a far more drastic increase in the money supply. In aggregate, the base money supply has increased by 22x since 1984. And it is not without consequence. As a function of quantitative easing, the US economy now sits further out on the same fragile ledge that existed during the financial crisis in 2008.

Source: Federal Reserve Economic Data (FRED)

If you believe the developed world is not in a precarious situation or does not rely on a monetary foundation similar to Venezuela’s, I would respectfully point to the Fed and its historical track record. Blind faith placed in this institution lacks all common sense. Consider the following quote from a resident Fed economist during the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis, at a time when the Fed was in the middle innings of creating $3.6 trillion new dollars as part of quantitative easing:

I want to just emphasize that I think the gaps in our understanding of the interactions between the financial sector and the real sector are profound.

Associate Economist, US Federal Reserve[47]

An honest review of history demonstrates the ill-suited temperament of those put in charge of managing central banks. While admitting profound gaps in their ability to understand the implications of actions taken on the real economy, the response was to continue down the same path, printing even more money and expecting a different result—with no credible reason as to why. The printing of money causes the currency to deteriorate over time until it ultimately fails completely. Now, as the world faces the consequences of the response to the last crisis, individuals have a choice between two great contrasts: a centrally managed currency designed to lose its value or a decentralized currency with a fixed supply. The latter comes with a cost in the form of energy consumption, but the positive externality will be long-term economic stability provided by a form of money that cannot be printed.

Economic Stability via Energy Consumption

Future economic stability is why there can be no fundamentally more important source of energy demand than the security of bitcoin’s monetary system, especially as central banks print more and more money. If you wait to see the obvious signs of hyperinflation, you will have waited too long. But Venezuela is not just an example of what transpires due to hyperinflation. It is a living example of the importance of energy production to the functioning of society. Some energy input is required to produce everything we consume in our daily lives. The coordination of those energy inputs is dependent on the reliability and stability of the money we use.

Ignore your morning coffee for a minute and think about the basics: clean water, sanitation, food, gasoline, electricity, medicine, basic healthcare, etc. The coordination of resources to deliver these services is dependent on a functioning form of money. When a monetary system breaks down, social coordination and even the social fabric of society begin to go with it. If the basis of all trade is energy, and if money is necessary to coordinate trade, the highest and best use of that energy should first be to protect the monetary system. Put your proverbial oxygen mask on first and then shift to dependents. Secure the money—the foundation of trade—and then focus on all of the derivatives.

Any concerns about the amount of energy bitcoin consumes or will consume is a red herring. It is not that electricity that could otherwise power homes should be sacrificed. Instead, it is that the electricity to power those homes will no longer be produced if a reliable form of money does not exist to coordinate economic activity and facilitate trade—just as what happened in Venezuela. In practice, bitcoin will not compete for energy resources that fuel our economy’s basic productive and consumptive functions in a zero-sum way. Instead, bitcoin’s function as a currency system will ensure that those very energy needs can continue to be fulfilled.

What would be regrettable for society is if more countries were to deteriorate into Venezuela-style economic and humanitarian disasters, where basic health and human services could not be reliably provided. The goal here is not to present a dystopian vision of the future but to articulate the importance and interconnectedness of the functions of money and energy in complex, highly specialized economies.

If it prevents even one more tragic incidence of hyperinflation, the energy consumption required to mine [bitcoin] will be the best bargain humanity ever got.

Bitcoin represents a backup switch to legacy currencies that are failing, and it is soon to be the primary engine powering both local and global trade. Setting aside the systemic risks that currently plague the US and global financial systems, bitcoin is a fundamentally more sound monetary system from the ground up, secured by the production and consumption of energy. You do not have to believe that the dollar’s fate will be that of the Venezuelan bolivar to recognize the importance and interplay between the stability of money and the production of energy resources. The risk inherent in even the possibility of hyperinflation is so negatively asymmetric that the price of bitcoin’s energy consumption is of small relative cost.

Bitcoin will consume any and all energy resources necessary to secure its monetary network, which is inherently driven by the base demand to hold it as a currency. Every ounce of energy bitcoin uses is devoted to securing its fixed supply and clearing transactions for final settlement. There is no waste. The more people that value the long-term stability bitcoin provides, the more energy the network will consume in total. In the end, this consumption will ensure all other derivatives of energy consumption will continue to be fulfilled, which is why there is no more important long-term use of energy than securing the bitcoin network. Put a price on economic stability and the economic freedom a stable monetary system provides. That is the true justification for the amount of energy bitcoin should and will consume. Everything else is a distraction.

-

Alex Hern, “Bitcoin’s Energy Usage Is Huge—We Can’t Afford to Ignore It,” The Guardian, 17 January 2018. ↩

-

Christopher Malmo, “One Bitcoin Transaction Consumes as Much Energy As Your House Uses in a Week,” Vice Media, 1 November 2017. ↩

-

BitInfoCharts, “Bitcoin Hashrate historical chart,” September 2017—August 2019, accessed 15 August 2019. ↩

-

“2015 RECS Survey Data,” Residential Energy Consumption Survey, US Energy Information Administration. ↩

-

Friedrich A. Hayek, The Road to Serfdom, condensed version (Reader’s Digest, April 1945). ↩

-

Leonard E. Read, “I, Pencil: My Family Tree as Told to Leonard E. Read,” The Freeman (December 1958). ↩

-

Milton Friedman, “The Power of the Market,” Free to Choose, volume 1, PBS, 1980. The lesson of the pencil begins at 15:40. ↩

-

Emily Sandys, “Venezuelan Crude Oil Production Falls to Lowest Level Since January 2003,” Today in Energy, US Energy Information Administration, 20 May 2019. ↩

-

Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, “Adjusted Monetary Base (DISCONTINUED),” retrieved from Federal Reserve Economic Data (FRED), Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, July 2019. ↩

-

Minutes of the Federal Open Market Committee, a joint meeting of the Federal Open Market Committee and the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Washington, DC, 9 August 2011. ↩

-

Saifedean Ammous, “The Problem Bitcoin Solves,” The Spectator, 10 November 2018. ↩