Chapter Six

Bitcoin Cannot Be Copied

(Originally published on 2 August 2019)

Alchemy

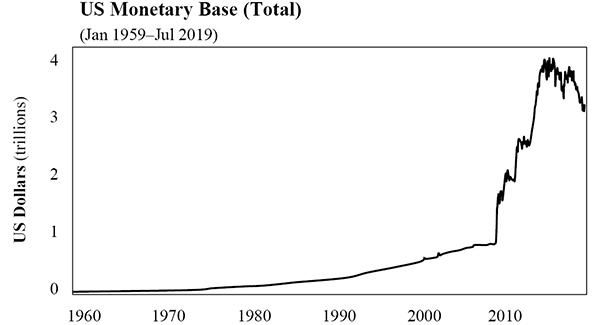

As kids, we all learn that money doesn’t grow on trees. However, despite this timeless wisdom, we have become conditioned at a societal level to believe that it’s not only possible but that it’s a normal, necessary, and productive function of our economy—specifically the practice of printing massive amounts of money, the modern equivalent of money growing on trees. Ever since the Great Financial Crisis, it has become an uncomfortable fact of life. Before bitcoin, the privilege of creating new money out of thin air was reserved to global central banks, including the Federal Reserve.

Source: Federal Reserve Economic Data (FRED)

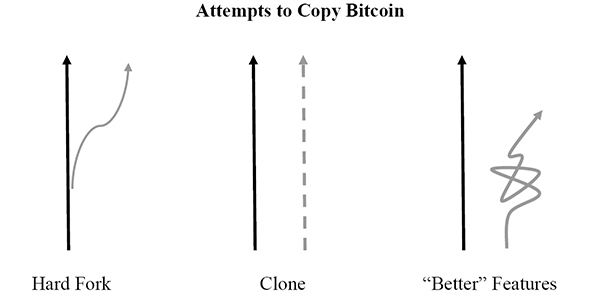

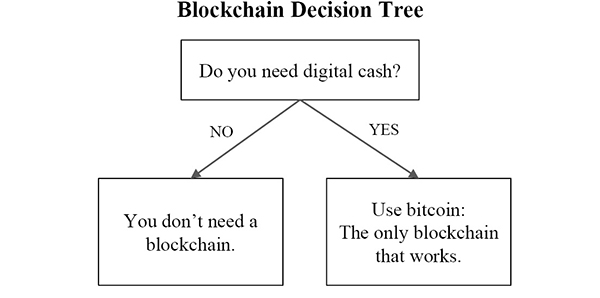

Bitcoin was specifically created to solve this problem—the problem of printing money. With a fixed supply, bitcoin provides a form of money that everyone can use and one that forever eliminates the ability for anyone to create more units of the currency arbitrarily. However, since the emergence of bitcoin, every Tom, Dick, and Harry seems to think that they too can create money. At a root level, this is the audacity of everyone who attempts to create a copy of bitcoin. Thousands of cryptocurrencies have flooded the scene, each with some promise to improve upon a perceived limitation in bitcoin. Whether by hard-forking out of consensus (Bitcoin Cash), cloning bitcoin (Litecoin), or creating a new protocol with “better” features (Ethereum)—to name a few—each is an attempt to create a new form of money. If bitcoin could do it, why can’t we?

And here we collectively sit—in 2019, as of the time of writing—witnessing the monetization of an economic good (bitcoin) on the free market for the first time since gold emerged as money over thousands of years. Rather than pausing to contemplate the weight of this reality or attempting to understand how or why it is possible, many people skip right past bitcoin and instead focus their attention and efforts on some derivative or some way to solve a problem they didn’t see in the first place. Everyone wants to get rich quick, and so long as there is money, there will also be alchemists. Those who attempt to copy bitcoin are our modern-day alchemists.

The alchemists assert that bitcoin is too slow, so they create a “faster” copy. Or that bitcoin lacks the capacity to handle the volume of transactions required to support the global economy, so they create a copy with “greater” scale. Then they declare that bitcoin is too volatile to be a currency, so a “more stable” version is created. It goes on and on. Next, it is that bitcoin is too rigid and needs to be more programmable, so a copy that is “more flexible” is introduced. The alchemists often even tell people that their creation is not money but instead a vehicle for “payments” or a “utility token” or a “global computer fueled by gas.” At the same time, a vision of a world with hundreds, if not thousands, of currencies is sold to unassuming victims. It is all noise, but make no mistake, in each case, it is the alchemist’s attempt to create money.

Bitcoin’s Value Function

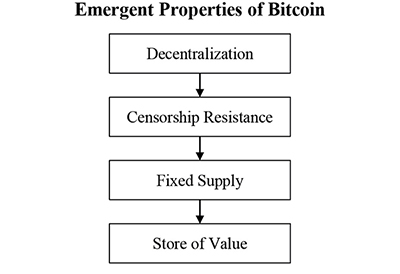

If an asset’s primary (if not sole) utility is in its exchange for other goods and services, and if it does not have a claim on the income stream of a productive asset (such as a stock or bond), it must compete as a form of money and will only store value if it possesses credible monetary properties. With each “feature” change, those who attempt to copy bitcoin signal a failure to understand the properties that make bitcoin valuable or viable as money—specifically that bitcoin’s value derives from the fact that the rules are not subject to arbitrary change. When bitcoin’s software code was first released, it was not money. To this day, bitcoin’s software code is not money. You can copy the code tomorrow or create your own variant with a new feature and no one who has adopted bitcoin as money will treat it as such. Bitcoin has become money over time only as the bitcoin network has developed emergent properties that did not exist at inception and that are next to impossible to replicate now that bitcoin exists.

These properties emerged organically and spontaneously as individual economic actors all over the world evaluated bitcoin and decided to store a portion of their wealth in it. As bitcoin’s value increased, it became decentralized. As it became decentralized, it became increasingly difficult to alter the network’s consensus rules or to invalidate or prevent otherwise valid transactions (often referred to as censorship resistance). Notably, it became ever more difficult—if not impossible—to change the rules or incentives that enforce bitcoin’s fixed supply. While there remains reasonable debate as to whether bitcoin is sufficiently decentralized or sufficiently censorship-resistant, there are other considerations less subject to debate:

- Bitcoin represents, by far, the most decentralized and censorship-resistant monetary system in the world today, whether compared to traditional currencies, other digital currencies, or commodity monies like gold.

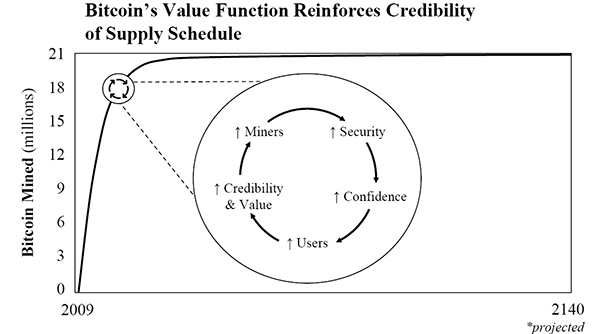

- Bitcoin derives its value because it is decentralized and because it is censorship-resistant; it is these properties that secure and reinforce the credibility of bitcoin’s fixed supply of 21 million (i.e., why it is an effective store of value).

- Bitcoin becomes increasingly decentralized and increasingly censorship-resistant as its value increases and as it scales at all levels of the network.

- Repeat—steps 1-3 create a positive feedback loop.

Economic Systems Converge on One Form of Money

Economic systems converge on a single form of money because the utility of money is liquidity and exchange rather than consumption or production. Every other fiat currency, commodity money, or cryptocurrency is competing for the exact same use case as bitcoin, whether it is understood or not. When evaluating monetary networks, it would be irrational to store value in a smaller, less liquid, and less secure network if a larger, more liquid, and more secure network were accessible. For example, if you worked for two weeks and your employer offered to pay you in a form of currency accepted by one billion people worldwide or a currency accepted by one million people, which would you choose? Would you request 99.9% of one and 0.1% of the other, or would you take your chances with your billion friends? If you are a US resident but travel to Europe one week a year, do you request that your employer pay you 1/52nd in euros each week or take your chances with dollars? The practical reality is that almost all individuals store value in a single form of money, not because others do not exist but rather because it is the most liquid and widely accepted asset to facilitate exchange within their local economy.

Anyone with Venezuelan bolivars or Argentine pesos would opt in to the dollar system if they could. Similarly, anyone choosing to speculate in a copy of bitcoin is making the irrational decision to voluntarily opt in to a less liquid, less secure monetary network. While certain monetary networks are larger and more liquid than bitcoin today (e.g., the dollar, euro, yen), individuals choosing to store a percentage of their wealth in bitcoin are doing so, on average, because of the conclusion that its fixed supply represents a more secure long-term store of value. And, because of the expectation that others (e.g., a billion soon-to-be friends) will come to the same conclusion and also opt in, increasing liquidity and trading partners.

Decentralized → Censorship-Resistant → Fixed Supply → Store of Value

Credible Monetary Properties

Most individuals who create digital currencies neither accept nor admit that what they are creating has to be money to succeed, while those speculating in these assets fail to understand that monetary systems converge on one medium or naively believe that their currency can outcompete bitcoin. None can explain how their digital currency of choice becomes more decentralized and more censorship-resistant, or develops more liquidity than bitcoin. In practice, no other digital currency will likely ever achieve the minimum level of decentralization or censorship resistance required to have a credibly enforced monetary policy.

Bitcoin is valuable not because of a particular feature but because it has achieved finite, digital scarcity, through which it derives its store-of-value property. The credibility of bitcoin’s scarcity (and monetary policy) only exists because it is decentralized and censorship-resistant, which in itself has very little to do with software. In aggregate, this drives incremental adoption and liquidity, which reinforces and strengthens the value of the bitcoin network. As part of this process, individuals are simultaneously opting out of inferior monetary networks. This is fundamentally why bitcoin’s emergent properties are next to impossible to replicate, and it is why bitcoin cannot be copied or outcompeted. Bitcoin already exists as an option, and its monetary properties become stronger over time (and with greater scale) at the direct expense of inferior monetary networks.

However, one would likely never come to this conclusion without first developing their own understanding of the following: (1) that bitcoin is finitely scarce; (2) that bitcoin is valuable because it is scarce; and (3) that economic systems converge on one form of money (i.e., one monetary network and system) to facilitate trade. You may come to different conclusions, but this is the appropriate framework to consider when contemplating whether it is possible to copy (or outcompete) bitcoin rather than a framework based on any particular feature set. It is also important to recognize that conclusions drawn by any one person have very little, if any, bearing in the equation. Instead, what matters is what the market consensus believes and what the market converges on as the most credible long-term store of value.

Source: The Bitcoin Standard by Saifedean Ammous

The empirical evidence (price and purchasing power) demonstrates that the market continues to determine that bitcoin is different, despite a significant amount of noise. Before speculating, try to understand why bitcoin works and why it is unique. When someone inevitably tells you about a “better” bitcoin or some differentiating feature, remember that the market, which has come to this same crossroad many times over the last decade before you, has considered those trade-offs and chosen bitcoin over the rest of the field for very rational reasons.

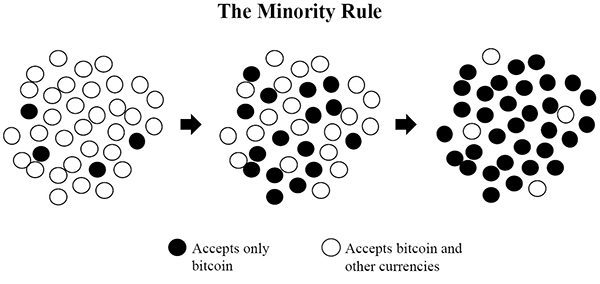

The Minority Rule

Nassim Taleb writes about how a very small intransigent minority can force its preference on the majority, referring to this phenomenon as “the minority rule” and explaining why “The Most Intolerant Wins.”[20] Monetary systems are a perfect example of this phenomenon. If a very small minority converges on the conclusion that bitcoin has superior monetary properties and will not accept another form of currency as money, while market participants with less conviction accept both bitcoin and other currencies, the intolerant minority wins. This is exactly what is happening in the global competition for digital currency supremacy. A small minority of market participants have determined that only bitcoin is viable, while at the same time rejecting the monetary properties of all other digital currencies. Because of its intransigence, the minority slowly forces its preference on the majority.

In the world of digital currencies, diversifying by picking the field is the equivalent of letting the crowd choose what your future money will be while resigning yourself to only a fraction of what you otherwise would have saved. Evaluate the trade-offs, anchor yourself in the fundamentals, and consider the minority rule before trading your hard-earned value for a perceived get-rich-quick flyer that you do not understand. Money doesn’t grow on trees.

Bitcoin is a remarkable cryptographic achievement, and the ability to create something that is not duplicable in the digital world has enormous value.

former CEO and executive chairman, Google[21]

“Bitcoin is a remarkable cryptographic achievement, and the ability to create something that is not duplicable in the digital world has enormous value.”

-

Nassim N. Taleb, “The Most Intolerant Wins: The Dictatorship of the Small Minority,” Incerto (blog), Medium, 19 August 2016. ↩

-

Eric Schmidt and Jared Cohen, “The New Digital Age: Authors Eric Schmidt and Jared Cohen in Conversation with Facebook’s Sheryl Sandberg,” interview by Sheryl Sandberg (Mountain View, CA: Computer History Museum, 3 March 2014), catalog number 102740112. ↩